Nancy Reagan and David Hasselhoff Walk Into A Bar…

Or the problem with teaching kids to just say “no”.

Or the problem with teaching kids to just say “no”.

Along with fresh pencils and clean backpacks comes a renewed interest in child abuse prevention…as if the start of school coincides with a rise of predatory behavior. (There is no such correlation.) A common theme in that programming is the idea of “no” as a tool to keep kids safe, as mentioned in a recent story on NPR. While it might seem like an urgent lesson at first glance, parents and caregivers should look at “no” a bit more critically.

In In 1982 First Lady Nancy Reagan visited an elementary school in southern California. One of the students asked Mrs. Reagan what she should do if offered drugs. Mrs. Reagan replied, “just say no”. It was the perfect soundbite. And a year later when the DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance and Education) program debuted in schools, “just say no” became one of their slogans. “Just say no” was DARE’s most well-known program.

If only it worked.

There are several critiques of “just say no” beyond the obvious: the program did not reduce drug use among children. But one of the central criticisms was that DARE placed responsibility on the child to keep themselves drug-free. No tools (other than to “just say no”) were given to kids. How exactly does an elementary school age kid “just say no” to an older sibling, the cool guy in the neighborhood or the downstairs neighbor who promises them something tantalizing?

…which makes you wonder why tips like just saying “no” are still used. Is “no” an essential tool for kids to understand consent? The executive director of a child abuse non-profit thinks so. In the NPR story, she says “the meaning of no” is “the foundation of consent,”. According to RAINN (the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization) however, there are many ways to give consent and consent does not need to be verbal. Consent, by its definition, is agreement of all parties to engage in an activity.

Yet, the word “no” is verbal. It isn’t body language or gut instinct; it’s a spoken one syllable word. There aren’t any other ways to categorize the word “no” except as a verbal statement. Yet, consent is agreement among everyone. The idea of “no” as the foundation of consent, then, is problematic because it speaks to the singular action of one person. So, ‘no’ cannot be the foundation of consent. The foundation of consent is consensus, verbal or otherwise.

But teaching kids to say “no” is problematic for other reasons.

How many kids do you know who would say “no” to a trusted adult who is doing something they shouldn’t?

The majority of children who have been sexually abused are hurt by a trusted adult, someone they know. Predators are trusted adults for reason! Even my 7 year old who has been hearing about different kinds of touch and bodily autonomy for years might not say “no” to her babysitter…for many reasons. Not least of which is that touch can be confusing. If something feels good, a “no” can be even harder to say out loud.

Is something else knocking around in your brain related to “no” and consent? For me it was this:

Children cannot consent to sexual activity.

Consent laws vary but generally it is agreed that children (and “child” can be defined differently in different states) are not developmentally able to make informed choices about many things, including sexual behaviors. They are also, of course, never in a position of equal power with an adult. And, RAINN reminds us, consent can only happen among people who have equal “standing” with each other.

Teaching kids to say “no” is dicey, too, because of how childhood trauma can affect the brain. Children’s brains are especially vulnerable to physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect. Trauma can impact a child’s brain including decreasing the size of the-

¶hippocampus (affecting learning and memory),

¶corpus callosum (affecting emotion, impulse and arousal as well as l/r brain communications),

¶prefrontal cortex (decision-making, behavior, balancing emotions and perception)

Are we really teaching already vulnerable kids their “no” can save them from future hurt?

Teaching kids to say “no” today is as insensitive, unfair and dangerous as it was in 1985 when I was a kid. Child sexual abuse is an epidemic. It is a public health crisis. It is not the fault of children. Nor should kids be responsible for keeping themselves safe and healthy, even in the seemingly innocent way of teaching them to say “no”.

So what should we be teaching?

We need to teach adults to respect a child’s bodily autonomy. American adults micro-manage children. From scooping up toddlers to helicopter parenting on the playground, parents are always right there. But kids’ bodies are their own. They have the right not to be hugged or kissed, for example, even by relatives. When kids understand their bodies are their own, they listen to and show respect for their body as they learn what it needs and wants.

We need to teach parents and caregivers that “what feels good to us isn’t always good for our children,” as writer Jessica Lahey says in her book, The Gift of Failure. Kids don’t need rescuing. They need “parenting for autonomy”: to be allowed to forget their lunch, leave a jacket behind, not be reminded of homework. Teaching children to listen to their bodies and respecting their “no” are are ways parents can encourage emotional language skills, a growth mindset and self-efficacy.

We need to teach healthcare professionals that childhood trauma like sexual abuse can have long term consequences on health and wellness. Dentists to dermatologists — and every healthcare provider in between — should know the facts of childhood trauma and how trauma might present in children AND adults. Often providers are with us for life. Our days outside appointments are as relevant to our good health as time on an examination table.

We need to teach teachers and administrators the signs of childhood trauma. And that hidden signs like acting out in class, suicidal thoughts and repeated absences are not always “bad behavior”. School counselors know these things but sometimes a beloved teacher does not.

We need to teach mental health professionals that childhood trauma is common. But trauma like sexual abuse is not a mental health disorder. Survivors, no matter their age, don’t want to be seen as hapless victims or scarred for life. They don’t want pity, judgement or quick prescriptions. They do want to be listened to and respected as experts on themselves.

Teaching a child their “no” may keep them safe is as myopic as teaching women to carry car keys between fingers. These tired tropes of prevention shelve responsibility on the individual. An individual who, incidentally, is not at fault for someone choosing to hurt them. Have we learned nothing after urging kids to “just say no” to drug dealers next door? But, thirty years later, it’s exactly what prevention experts are still teaching kids: that their “no” can protect them.

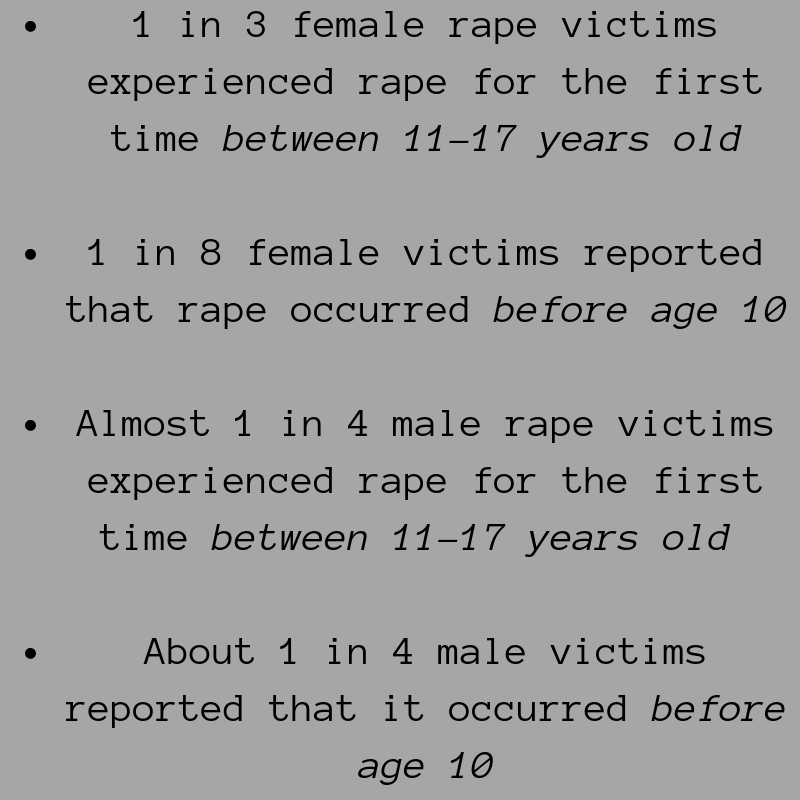

According to the NPR story more than 58,000 children were sexually abused in the U.S. in 2017. The 150+ page report is dense so allow me to share different statistics from the CDC instead.

The majority of children are abused by someone they know, often a trusted adult. These are children who may or may not have been taught to say “no”. But more than likely, at some point, they will blame themselves for their abuse. And perhaps, too, shame themselves for not saying “no”. I hear that version of the “just say no” story everyday. It’s heartbreaking.

Teaching kids their “no” may matter, that the “meaning behind the no” (whatever is intended by that vaguery) is the “foundation of consent” is to offer a dangerously false sense of protection.

We imagine “no” like we do domestic violence protective orders: a magical intervention that will end the chance of harm. But a “no” is just as worthless as a piece of paper is to stop a bullet when it comes to someone intent on harm.

“Just say no” was a colossal failure. Millions of dollars were spent on educating children but in the end, kids were not less likely to use drugs. Let’s not make the same mistake today when we teach kids how to protect themselves from sexual abuse. These models of “prevention” are broken. These models of “prevention” should be thrown out.

Elizabeth M. Johnson MA is a writer and podcaster based in Durham, North Carolina. She writes about trauma, relationships and how we make decisions. Sign up for her Substack here or be social @EMJWriting.

.